To Dave Hoekstra and most of the other 50,000-plus young people who packed old Comiskey Park on July 12, 1979, Disco Demolition was nothing more than a chance to have a little goofy fun on a hot summer night and blow off some steam.

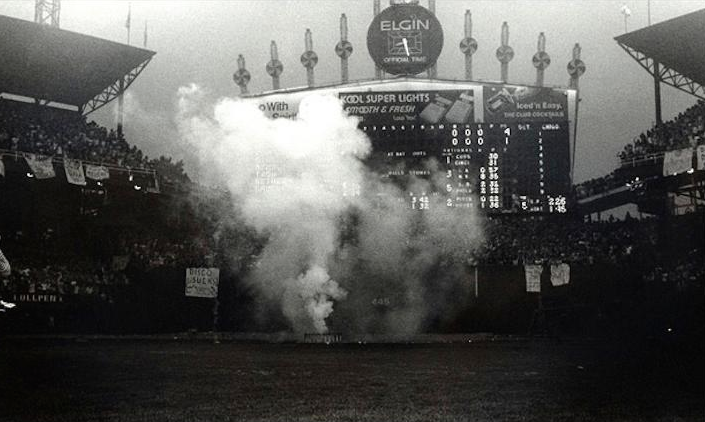

Enter Steve Dahl, a pitch-perfect pied piper for Chicago’s rock and roll rebels: Right on cue, the 24-year-old recently-hired morning host from WLUP FM 97.9 exploded a box of disco records between games at a White Sox double-header with the Detroit Tigers. Suddenly thousands of rowdy fans stormed the field. The ensuing pandemonium, which forced the White Sox to forfeit the second game, made worldwide headlines the next day.

In the 37 years since that night, the episode has taken on mythic proportions. Depending on your point of view, it was either the most successful radio promotion of all time, or a blot on the White Sox and the city of Chicago, or a turning point for disco and pop culture in the Midwest (if not America), or a shameful spectacle of racism and homophobia run amok. To some, it may have been all of the above.

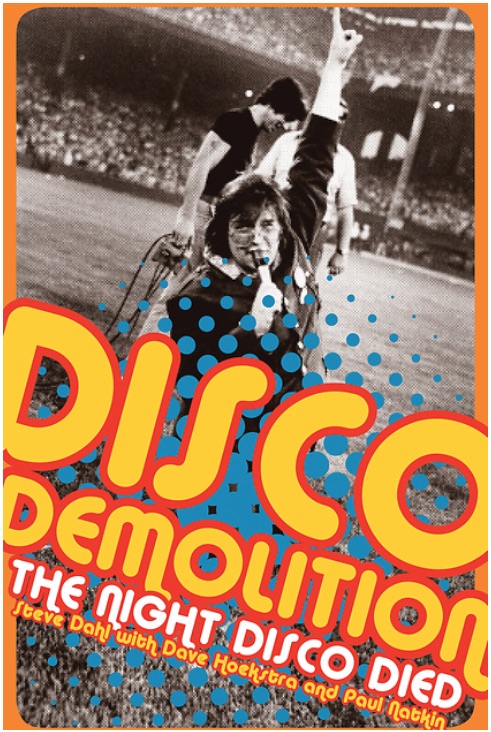

Hoekstra, now a celebrated Chicago journalist and author, thoughtfully considers the myth and the reality of the era in Disco Demolition: The Night Disco Died, just published by Curbside Splendor and available on Amazon. Illustrated with Paul Natkin’s archival photos, the 200-page hardcover features interviews with some 50 key figures, including a wide array of witnesses and many who were directly involved in one way or another.

Over the two years he researched the book, Hoekstra said, one of his most surprising revelations involved the opposite trajectories of his two protagonists.

While Disco Demolition proved a career-defining moment for Dahl, it marked a dead end for Mike Veeck, who organized the event for the White Sox. Although Veeck’s famous father shouldered much of the blame for the publicity stunt gone awry, Hoekstra said, the son’s career fell apart after that.

“Mike was living in the populist shadow of his father, Bill Veeck, Jr., and that was already a daunting thing for him,” Hoekstra told me the other day. “Mike really wanted a career in baseball and this event ruined that. His maverick father already wasn't popular with MLB owners, and then Disco Demolition came along. As Mike said in the book, he could only get hired by soccer teams because ‘apparently they like riots.’

“Adding to that drama, like any good father, Bill Veeck took the hits for his son.”

It takes until Chapter 15 (155 pages into the book) to reach the best part — a vivid account of the events on the field and behind the scenes. Hoekstra does a masterful job evoking the excitement, the giddiness and, at times, the terror of that historic night from all angles.

Even so, is the world still interested in Disco Demolition — or Steve Dahl — 37 years later? According to the latest Nielsen Audio ratings, Dahl’s weekday afternoon show on Cumulus Media news/talk WLS AM 890 is tied for 27th place with a 1.5 percent audience share. To his credit, at age 61, sober, and a grandfather several times over, Dahl is still in the game. But clearly everything and everyone else around him has changed.

What makes the book fresh and relevant today, Hoekstra said, is the “sociological approach” he took to recast a familiar story.

“I felt it important for readers to know about Chicago neighborhoods and Chicago radio of the period,” he said. “Late 1970s Bridgeport — Comiskey, International Amphitheatre, Stockyards, etc. — was a pop culture petri dish for this event. That's why I interviewed Bridgeport chef Kevin Hickey, the late Jack Schaller [owner of Schaller’s Pump], and also why I went sort of deep into radio characters.”

Hoekstra writes with particular authority about the local radio scene, including the generational divide Dahl and partner Garry Meier so skillfully exploited with the city's reigning king of morning drive, Wally Phillips. Mitch Michaels, Bob Sirott, Les Grobstein and Jeff Schwartz add much to Hoekstra’s insight (although one glaring gaffe was a passing reference to “the late Randy Michaels,” who’s still very much alive).

Not everyone Hoekstra interviewed dismisses those who later claimed Disco Demolition carried undertones of racism and homophobia. In hindsight, there was plenty of anger and prejudice in the crowd toward a music genre closely associated with blacks, Latinos and gays. One asks: Is burning records that much different from burning books?

But those few voices of dissent are overwhelmed by Dahl’s vehement denials and those of people closest to him. "I'm worn out from defending myself as a racist homophobe for fronting Disco Demolition," Dahl writes in his introduction. “That evening was a declaration of independence from the tyranny of sophistication. . . . We were just kids pissing on a musical genre.”

In the end, according to Dahl’s wise and supportive wife, who gets the last word in the book, Disco Demolition gave what mattered most. Says Janet Dahl: “Everybody craves validation."